Introducing Personality Maps.

Personality Maps, Part IV: A new way to navigate ourselves and other people.

For many of us, learning our personality type is a revelation. We go from glimpsing ourselves and others in fuzzy black & white to seeing a spectrum of colorful characteristics.

But our new Technicolor lens comes with a blindspot:

Personality models can’t see outside their boxes.

As we explored in the last essay, the fundamental limitation of any personality model is its boxed-shaped results like “ISTJ,” “Enneagram Four,” or “Introvert.”

The ideas may be helpful, but the boxy shape tends to blind us to how other outside-the-box forces shape us like our environment or social group.1

For everyone who embraces a personality box as empowering, another rejects it as limiting.

These limitations turn a nice idea like using personality to help diverse humans play their unique parts in harmony with others into a mythical ideal.

All the world’s a stage.

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.”

— Willam Shakespeare in As You Like It.

In contrast to much of modern life, there are corners of the world where we naturally embrace our roles in concert with others:

Do actors decry the limitations of playing Othello? Or rattle off another actor’s lines after losing track of the part they were playing?

Do third-basemen complain about being so confined to such a small field area?2

Why don’t the violinists rise up against the repression of the more dominant brass?

When grounded on a field or stage, we put on our role as quickly as we might slip on a jersey. We can see how our roles play together, so we hardly need to think about them, let alone fight about them.

We’re players without a stage.

But in “real life,” most of us can’t look around and see where we’re playing, and neither can our coworkers, partner, or friends. Most modern life and work happens in a placeless void — there’s no left field, center stage, here, or there.

So, of course, we have to think about our positions a lot.

We employ increasingly detailed categories like job titles, Org. Charts, social identities, and of course, personality models. But the larger and more diverse our group, the more role confusion and turf wars lurk around every corner.

Using personality models to compensate for our lack of positional awareness is like playing Chess or Monopoly with the pieces but no game board. Or baseball with players and stats but no field.

Life’s not a game (or is it)?

I can anticipate a reasonable objection: it’s easier to play a role in a group when there are simple rules and the stakes aren’t so high as in real life, right? Well, not so fast:

First of all, we take our games and performances quite seriously. They’re a multi-billion dollar industry involving millions of people.

As any performer knows, games and shows are simple to watch but not to play. The difference is the ability to watch: we can spot a great goalkeeper by watching them in front of a net. But try evaluating a programmer by watching them type away at their desk.3

Furthermore, for most of human history, most of life was equally watchable. Most everything played out in physical spaces with everyone playing easily identifiable parts. Shapeless, spaceless social media and knowledge work are modern phenomena we’ve yet to adapt to.4

We more easily embrace our parts in a game or performance not because they’re simpler or less risky, but because we instinctively know how to play together given a shared space.

Introducing Personality Maps

Personality Maps slide a Chaos-Map-shaped game board underneath any personality model. When we plot personality types and traits visually meaningful space, we get a few upgrades:

A map reveals that our personality isn’t all about us.

Unlike a personality model, a personality map requires thinking about the context first. For example, let’s look at just one part of the map:

The Chaos to the right of our map is where we find the unknown potential of whatever we’re mapping. In it, we might encounter:

Sci-fi-like or mystical visions for the future of humanity.

The seemingly impenetrable questions impeding game-changing innovations.

An existential threat to our company that no one seems to see or take seriously.

In encountering Chaos, we feel some amount of confusion, intrigue, dread, or exhilaration — sometimes all at once. Chaos doesn’t have a physical location, but it’s a real-enough psychological place that we know when we’re in it.

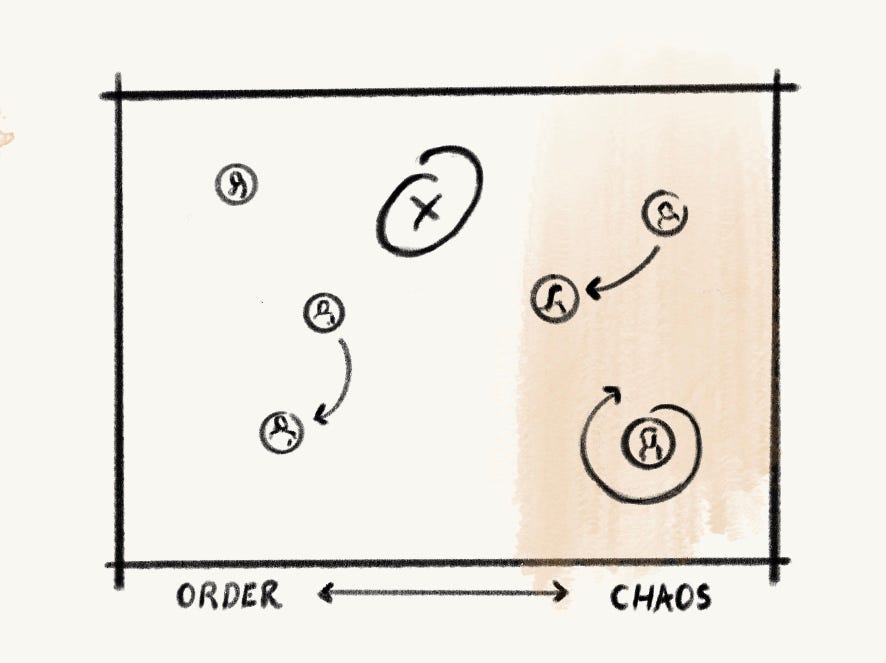

Those of us who personality models classify as “Intuitive,” “Open,” or “Type Five” are drawn towards the Chaos on the right like fireflies to light:

But those of us who personality models label as “Sensing,” “DISC S,” or “Type Six” usually like to keep a comfortable distance within more orderly environments.

Adding a few more layers to our map can reveal the location and movement of many other personality types and traits.

But even a single-axis map frames personality more like a GPS indicator for where we like to play in a specific scenario and not who we are all the time.

Our personality isn’t all about us — it only looks that way when we can’t see what’s around it.

A map can put us all together.

Maps make it possible to plot the position of any number of personalities (even from different models) in a shared context. Now that we have a field of play or gameboard to put our personality pieces on, we can use them as a playbook:

We can strategize about what parts of the work to pass off to whom, see where things are out of balance, spot gaps, and more.

In the final few essays in this series, I’ll map each of the popular personality models: Myers-Briggs Types, Big Five Traits, the Enneagram, and perhaps one or two others.

I hope to map each of them clearly and accurately, and that’s where I could use some help: If you’re a knowledgeable user of any of the above personality models, would you be willing to share your feedback with me as I map it out? If so, please let me know (and thank you in advance).

These limitations are common to all mental models that borrow the forms of science.

And why’s there no Vox article about how positions like “midfielder” or “point guard” are totally meaningless?

I don’t think that being a great designer, CEO, writer, stock trader, or any modern occupation requires more intrinsic skill than being a great player in a game or ensemble. The primary difference is that performance of the former is far more vague and subjective than the latter.

This is amazing stuff! What if we could do a better job visually displaying personality results as a meaning-making, self-organizing activity of the self interacting in response to their context?