Are personality types scientific?

Personality Maps, Part II: The proper role and limitations of science.

"Basically, they're like horoscopes." — Vice.

In pop science and corners of academia, the notion of personality types is scorned as old-fashioned, pre-science thinking.

(But if we scratch the surface of the clickbait hot takes, reports of the death of personality models by science are greatly exaggerated.)

While I believe that personality models are useful and necessary tools for transcending our darker default ways of patterning people, I don't think they're scientifically proven either – at least not in a double-blind, controlled, peer-reviewed study kind of way.

To me, the scientific critique of personality models brings up a more fundamental question:

Why would we expect personality models to be scientifically verifiable in order to be useful in the first place?

The limits of science.

Let’s begin with a few thinking prompts:

Is the best music or art created using the scientific method?

Watch the new documentary, Get Back, and look for science’s role in The Beatles’ creative process.

Do the most delicious meals come from double-blind trials?

Look into "New Coke" to see how badly basing a recipe off blind taste trials can go; And think about how master chefs don’t use recipes, effectively making their dishes scientifically untestable.

How can we know if we've met our soulmate without a scientifically valid assessment?

Try out an assessment to verify that question on a date or with your significant other and see how it goes.

Given the apparent absurdity of using science as the primary means to evaluate or create in these limited human scenarios, why do we feel the need for scientific validation before we model human personality holistically?

I'd suggest that the answer can at least partially be found in two pervasive misapplications of science: scientism and science consumerism.

Science vs. scientism.

Science and its sister, Technology, are the foundation and gods of our modern world. As modern, western humans, we can't help but feel like claims not backed by science are questionable. Fair enough.

But the crack in our thinking comes when we believe that science has – or someday could have – all the best answers. This line of thought leads to scientism - a belief that reasoning from observable, material reality is the preeminent path to truth and progress; That all other ways – from art to religion to philosophy – are somehow inferior.

"It is an odd sort of intellect which ranks matter before itself and attributes real being to matter but not to itself." — Plotinus.

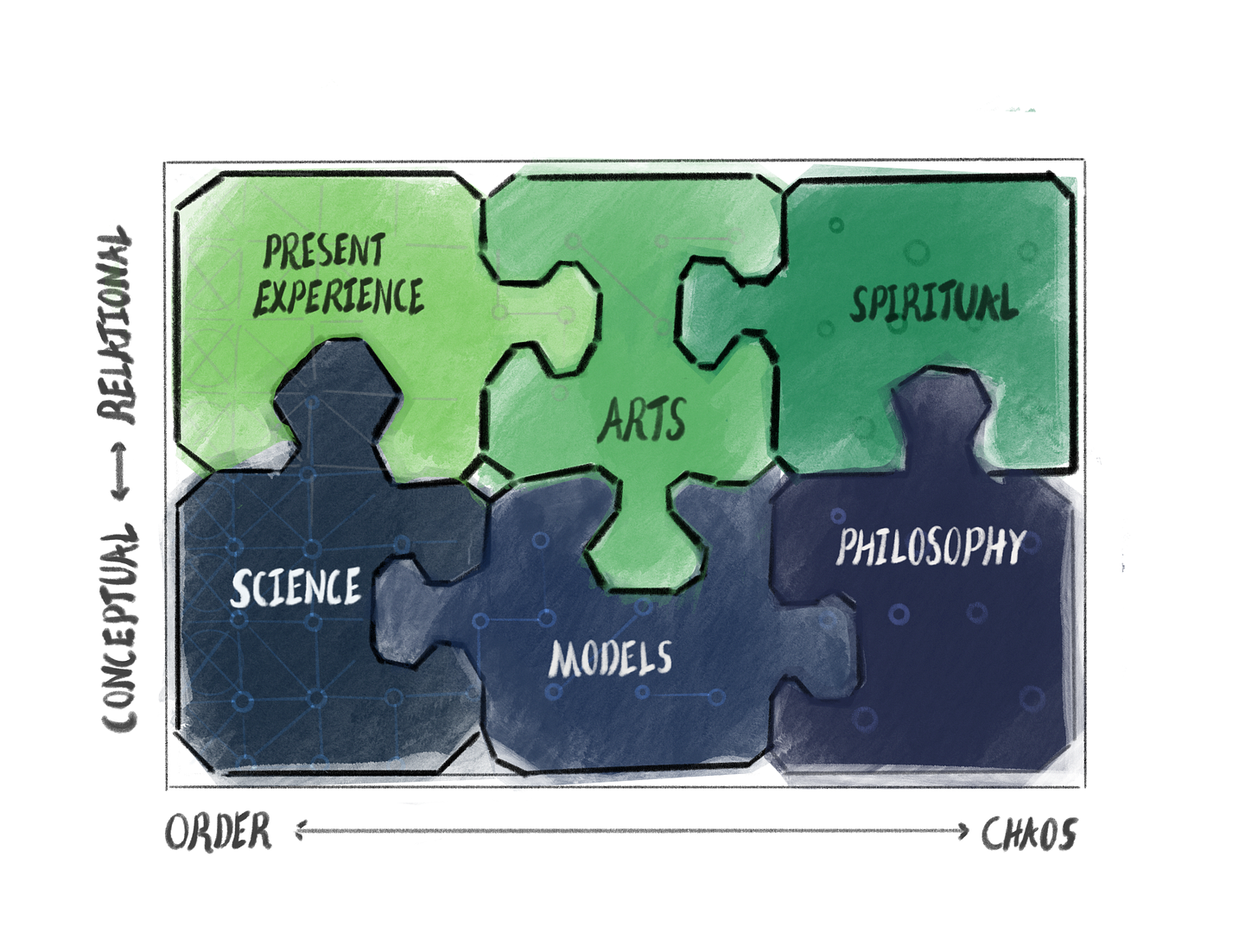

Science is one piece of a bigger puzzle.

At its best, science puts our real-life present experience of things under the microscope; It decodes and abstracts the material world into increasingly intricate concepts and powerful formulas that yield more precise, robust, and scalable methods.

Science alos helps debunk observable claims like these:

Phrenology: a bump on your skull in a particular place indicates talent for painting.

Zodiac: people born in July are more likely to adopt caregiver roles.

1940s advertisers: smoking cigarettes is just what the doctor ordered.

Should we also use science to test specific claims from personality models? Of course. But here's the dilemma we run into when applying it to big questions like personality:

Science is only as reliable as its questions are narrow.

Science advances by dispassionately decoding and testing observable reality from well-formulated questions. It operates best at a ground-level view of our present experience and proportionally less so at the tree level and not above the forest level.

(So far, applying science to too big human questions has resulted in the “replication crisis” where hundreds of psychological findings from foundational textbook studies like the Stanford Prison Experiment fail to replicate.)

Reliable science relies first on imagination.

The questions science rests on can only be asked after we have a theoretical framework for how things likely are and what they might mean.

But new theories, paradigms, and frameworks emerge from chaos — not from what we already know.

By definition, they require intuitive, imaginative leaps beyond what's currently known, observable, or predictable.

"The gift of fantasy has meant more to me than my talent for absorbing positive knowledge." — Albert Einstein.

Proper science with its data, logic, and methods contributes in service to and as a result of human imagination and creativity, not as an arbitrator of it.

But scientism quickly dismisses imaginative and useful paradigms like personality types as "unscientific."

Is this kind of misguided dismissal of an idea like personality types the end of the world? Probably not.

But given free rein and the right circumstances, scientism can lead to far more destructive practices like eugenics which used science to justify dismissing humans from the gene pool.

The science consumerism trap.

“More than 80% of dentists recommend Colgate" sells a lot of toothpaste.

Science sells — a fact those 1940s cigarette companies knew well.

Science sells as social currency, too: science on our side is a powerful buttress to our group identities. A "Believe Science" social media post instantly signals the political side someone takes on climate change or the Covid-19 pandemic. (But, broadcasting belief in science is clearly insufficient for persuading the broader public.)

Unfortunately, the personality-typing industry knows that science sells as well; They may caveat their claims in print but present their tests and data in a style and shape that looks remarkably like what we might get from our (hopefully) more scientifically-minded physician: assessments, charts, percentages, and prescriptions, and all.

I'm 67% introverted? It looks so precise. How could it not be perceived as scientific? (But who knows what that means compared with 62% introverted.)

The bar graph shows I'm highly neurotic; (That's bad, right, doc?)

An assessment that yields a sciencey-looking report along with prescriptive descriptions plays right into our vulnerability to science as a value signal.

A scientific veneer sells in the short term but opens a wide door for narrow scientific critique while attempting to offer more – not less – of what science can even see.

I think science is the wrong form and frame for something so human as personality. But, the more scientific-seeming the problem, the easier it is to sell the medicine.

A better question.

Using science as a primary frame for dismissing or promoting bigger-than-science ideas like human personality artificially narrows our perception; We trade the wonderful big picture and complexity of ourselves and others for one piece of the puzzle.

I think a better question than "are personality types scientific?" is something like:

Do personality models help us be more fully human and humane?

Answering this question requires considering our whole human experience in concert rather than fixating on one part.

Where do we go from here? I’ll leave you with two questions that we'll explore more in the next essay in the series:

Why do many sciencey and unsciencey people use science to dismiss personality types? In my experience, there's usually a human reason behind the critique: they or someone they love got stereotyped and treated in a less than human way by applying a personality model as if it was “textbook fact.” But what is it about personality models that lead people to place themselves and others in reductive, limiting boxes?

If we were to redesign personality assessments or models to look less like scientific assessments and reports, what might they look like? I tend to think they’d feel more like playing a game or an instrument and look more like art than statistics.

"Writing about music is like dancing about architecture."

– Martin Mull.

Along those lines, perhaps presenting human personality like science is like watching a movie in a spreadsheet.

I'd welcome your thoughts on these or any other questions around personality: leave a comment, send an email, or book a conversation anytime.

Special credit: while this is generally true of most essays, some of the specific ideas around personality types in this essay come from many conversations and project collaborations with my twin, Mark, who enjoys exploring and experimenting around personality models as much as I do.